This is the paradox of Zambia's "successful" middle class: they earn too much for aid but too little for comfort, trapped in a cycle where appearing prosperous costs more than they can afford. When over 70% of workers have no job security and a single family emergency can erase years of savings, what does it mean to "make it" in modern Zambia?

Living Paycheck to Paycheck in Lusaka

Agatha's bank account shows K2,000, her rent is K1,800, and it's due in five days—but she's heading to Lusaka's most expensive mall anyway. Agatha, a 33-year-old marketing officer, heads to the mall. Her petrol tank sits at half full; rent is due in 5 days. A WhatsApp message from her teenage nephew asks for school fees. Once she slides through the glass doors of East Park, her first stop is an overpriced cafe. The coffee and croissant combo drains more from her wallet. Though she can't afford it, she tells herself she deserves a taste of the wealth she has worked hard to earn this month. Deep down, however, Agatha knows the truth: one emergency could pull her back into the poverty she believed she’d escaped.

As of May 2025, the figure needed for a family of five to cover the cost of living in Lusaka stood at K11,272.97. This gap between stagnant wages and rising living costs reveals the core challenge: Zambia's middle class is built on shaky ground. Even those with the jobs and qualifications to seem well off are one misfortune away from falling back into poverty. Educational attainment and increased earnings offer the illusion of stability, yet the escalating costs from energy crises to inflation mean that middle-class survival is always precarious, tethered to a system that barely keeps them afloat.

When we think of financial struggle in Zambia, we often picture those living in extreme poverty—rightly so, since more than half of all Zambians fall into this category. But look closely at the middle class—the group commonly believed to have escaped hardship—and the reality is different. This class exists in a constant state of vulnerability, with their apparent security masking a persistent, quieter struggle. The cracks in our economy are most visible here, challenging the idea that anyone, even those in the middle class, is truly thriving rather than just surviving.

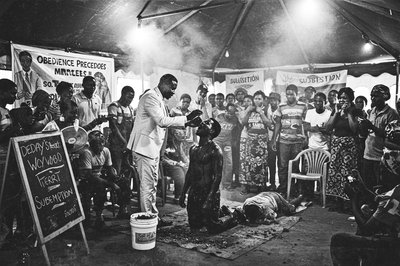

Zambia’s middle class carries a specific burden. They earn too much to qualify for aid, but not enough to live comfortably. In the very economy they’re told they belong to, a hidden tax exists: the cost of appearing successful. Where you live, the house you rent or build, the car you drive, the clothes you wear, the school your children attend, and the lifestyle you present—all come with a price. As salaries increase, so do expectations. Many end up spending more than ever, simply to prove they belong where they are.

Many would rather go into quiet debt than lose the performance of progress. It’s this pressure to maintain appearances—despite the reality of their finances—that leaves middle-class Zambians wondering what they truly have. Because with cash pouring out of them with each invoice and grocery trip, what else do middle-class Zambians have to prove their success than these symbols of status?

How Financial Shocks Destroy Middle-Class Dreams

Keeping up appearances is costly, but a single unexpected crisis is often more expensive. Many in the middle class have minimal savings; one emergency can wipe them out. A funeral, a hospital stay, retrenchment, or a broken-down car—especially one that doubles as a business tool—can erase years of careful budgeting. Sacrifice and saving may be undone in a moment, dragging a family back to square one.

In 2024, The Financial Times profiled Prince Nyirenda, a Zambian civil servant. Once a promising student, Prince had to drop out of high school after the sudden death of his father. He started over, found work as a driver, climbed the ladder slowly, and eventually bought a car, his symbol of arrival. But when relatives needed help with school fees, he had no choice but to sell it. Years of work, sacrificed in a moment.

In Zambia’s extended family system, the middle class doesn’t just carry its weight. The reality is, they carry the weight of many. The cultural and moral obligation of “black tax” means that anyone who appears to be doing well becomes a lifeline for those who aren’t. And with more than half the country living below the poverty line, there are always relatives in need. A cousin’s school fees, a sibling’s rent, groceries for an ailing aunt. The cost of being the one who “made it” is often paid again and again, until you haven’t made it at all.

Zambia’s community-based culture has long been a source of pride. In black tax, however, its foundational values—unity and ubuntu—are twisted. The successful are forever liable for familial situations they didn’t cause, while those dependent take no accountability. For them, there’s always a wallet to turn to—even as they drain it. White families inherit houses from their parents; black families inherit dependents.

Why 70% of Zambian Workers Have No Job Security

Ironically, the very jobs and salaries that define middle-class life in Zambia are often built on sand. This precariousness is reflected in job security statistics. According to a 2021 Labour Force Survey, only 26.8% of workers hold formal contracts. That means over 70% of the workforce lives with no guarantees. For Zambia’s middle class, job security is more illusion than reality.

And education offers no immunity. University degrees and professional titles don't shield you from short-term contracts, consultancy gigs, or underpaid government positions. According to the same Labour Force Survey, more than 85% of Zambians are employed in the informal sector. Even those in formal employment regularly face delayed salaries, wage stagnation, and abrupt restructuring. A payslip, once a symbol of stability, no longer guarantees a predictable life.

Civil servants, nurses, and teachers might be technically employed, but many can only survive by moonlighting, side hustling and sacrificing sleep. In the private sector, NGOs and media houses are revolving doors; staff constantly watch their backs. One organisational reshuffle can erase your middle-class identity—your job—almost overnight.

What Zambia's Struggling Middle Class Reveals About Our Future

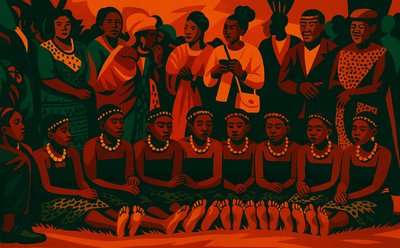

In a country where the majority live in poverty, the existence of a middle class has long served as a symbol of hope— a fragile promise that hard work could earn you a life of dignity. For many, it has been proof that Zambia is not solely defined by struggle, that there are people who are building, thriving, and dreaming. This underlying optimism has played a crucial role in shaping national aspirations.

But what happens when that symbol starts to crumble? The fragility of Zambia's middle class threatens to upend longstanding hopes for progress. As the foundation weakens, the truth of middle-class existence—perpetually on the brink—becomes unmistakable.

When the middle class begins to buckle under the weight of frozen wages, rising costs, and vanishing safety nets, we risk more than just personal collapse. The stability and aspiration that hold the centre together are threatened, with implications that ripple beyond individuals and families.

Because if those who “made it” are still barely holding on, what does that say about the rest of us? The answer may challenge the very belief in upward mobility that has fueled generations of hope.