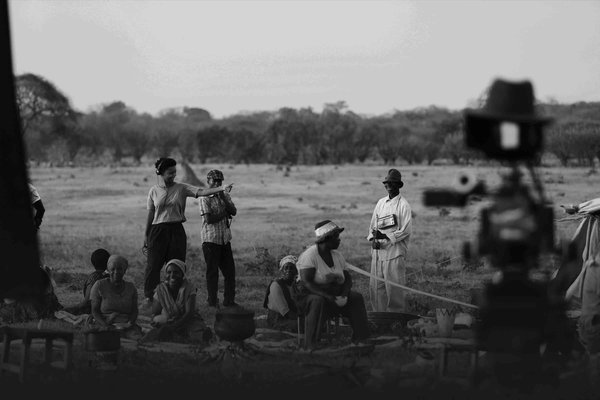

In her second feature, Zambian–Welsh filmmaker Rungano Nyoni transforms personal tragedy into a stark and surreal tale. On Becoming a Guinea Fowl follows Shula through funeral rituals steeped in contradictory emotions—mourning, gossip, performance—after she discovers her predatory uncle’s body. Drawing on her grandmother’s storytelling traditions, Nyoni delivers dry humour and magical realism, resisting over interpretation. Filmed in Zambia, the movie earned her Best Director Un Certain Regard at Cannes 2024. It is a powerful assertion of women’s voices, cultural rootedness and cinematic authority.

Rungano's film came to her in a dream.

She woke up in the middle of the night and said to herself, "I think I dreamed a movie." Still half-asleep but compelled to explore the possibilities further, she began writing immediately. The story she outlined took shape over several years, evolving into On Becoming a Guinea Fowl, the Zambian-Welsh filmmaker’s second feature film—a haunting, darkly humorous reflection on silence, complicity, and tradition. The film earned Rungano the Best Director Award in the Un Certain Regard section at the 2024 Cannes Film Festival—a prestigious category that spotlights films with unusual styles and non-traditional storytelling approaches.

The year she began drafting Guinea Fowl was an especially significant and difficult one. Rungano lost two family members she was close to: her grandmother and her uncle. Grief, layered with the demands of funerals—particularly for women—lingered in her mind. "Imagine doing all this work for someone you loved; now imagine doing it for someone you hated." The intersection of that discomfort and that tension is where the film begins.

Guinea Fowl opens with its main character, Shula, driving home from a fancy dress party. She is dressed as Missy Elliott in the music video for her Rain (Supa Dupa Fly) track. She spots something in the darkness and discovers her Uncle Fred lying dead on the roadside near a brothel he most likely visited that night. The image of Shula standing over her dead uncle in an oversized space suit and a bedazzled headpiece is striking—almost absurd. It has been widely interpreted as a comment on private versus public identity, diasporic dissonance, or as Rungano’s way of saying women in Zambia are not free. But Rungano shared that most people misinterpreted the outfit and read too much into it. "In the film, we don’t get to know Shula outside of the funeral, and she remains stoic throughout. With this outfit, her personality, life and sense of humour are allowed to flicker for a moment before giving way to the heaviness," Rungano shared.

Throughout my conversation with Rungano, it becomes clear that audiences misinterpreting her work has been a common occurrence, stretching back to her first feature film, I Am Not a Witch (2017). "It is alright for people to interpret my work differently than I intended," she says. "I just don’t want to hold the viewer’s hand and over-explain scenarios to them. I just want to make the film I want to see."

How Zambian Funerals Shaped Rungano Nyoni’s Darkly Comic Filmmaking

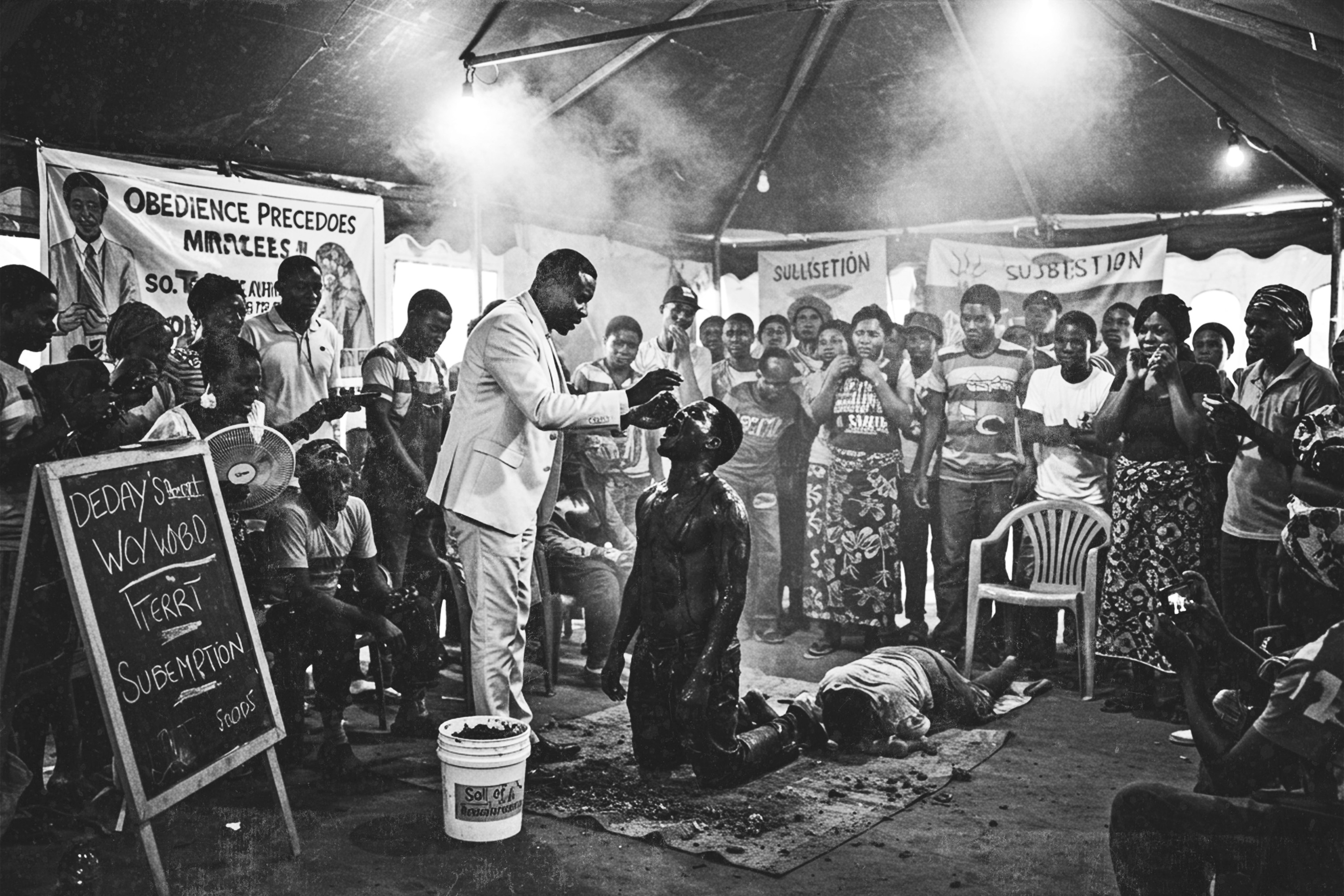

Rungano brings her signature blend of magical realism, dry, biting humour, and observations from Zambian funerals to Guinea Fowl. "Funerals in Zambia are full of contradictions," she explained. "They’re sad and overwhelming, but in some ways, they’re not really about the person who died. There’s gossip, family politics, food debates, and who’s cooking for the 500 people here? You’re mourning, but you’re also laughing. That contrast shaped the film."

As Guinea Fowl progresses, we learn that the deceased hurt a lot of people and was a sexual predator—Shula being one. While the family is aware of his crimes, she’s still the recipient of pressure to mourn him regardless. Shula is expected to put her ‘differences’ aside and conform to the performative side of Zambian funerals.

"I wanted to reflect on how difficult it can be to speak up," Rungano said. "Especially when you know no one will support you. There’s a reward for silence, socially and emotionally. Speaking costs you."

Finding Her Way to Film

A common misconception about the actress-turned-director is that she comes from a creative family, or that her upbringing nurtured her creative side. However, Rungano asserts, "We weren’t a creative or cinematic family. No one in my family was in the arts. Everyone had ‘proper’ jobs, but interestingly, the jobs they picked weren’t easy ones. People in my family tend to be stubborn, and I inherited that trait too and translated it into my career." Rungano studied business before accepting that film was her true calling. "I thought acting was my way in, and I studied acting, but I was a terrible actress," she shared. "I then tried producing before I found my place as a director."

Although Rungano insists that her background did not lead her to film, she notes another creative in the family—her sister, award-winning author Mubanga Kalimamukwento. The siblings share a similar journey: both initially pursued conventional professional paths before following their artistic callings. "A job in the creative world wasn’t an option for us growing up. That’s why I first studied business, and my sister studied law before we explored our creative curiosities."

Rungano credits her grandmother for influencing her storytelling style and her creative DNA. "My grandmother used to tell many stories, or utushimi, including fairy tales. They incorporate a lot of magic and music. I was trying to find a style that could be mine and not just copy anyone, so I looked to my grandmother," she shared. This influence is visible in both her films, which incorporate elements of magical realism and fairytale-like qualities that echo traditional Zambian storytelling.

Rungano’s great-grandmother makes her mark in another way—through the naming of her characters. The main characters in Guinea Fowl and I Am Not a Witch are called Shula, for Rungano’s great-grandmother. In both cases, what began as a placeholder stuck as filming progressed.

Why Rungano Nyoni Insists on Filming in Zambia

While Rungano has lived most of her life outside Zambia, her filmmaking instincts have always pulled her back. "I did not set out to only make Zambian stories," she admitted. "But whenever I sat down to write, Zambia came to me. Perhaps it’s my grandmother’s way of calling to me."

Still, Zambian stories have never been easy to fund or sell. Her early pitches were often met with remarks like, "This is too African." Even now, distribution across the continent remains a challenge. "My films are more accessible abroad than they are at home. That’s an African problem, not just a Zambian one," she said. "Distributors don’t think it’s worth the effort to showcase African films in Africa."

Despite this, she has doubled down and insists on making her films in Zambia and about Zambia, even though she admits that filming in the UK is significantly easier. Her work represents a growing wave of African filmmakers determined to tell their stories authentically, regardless of industry challenges.

She moved back to Zambia in 2024 with her husband and three-year-old daughter. "I wanted my daughter to have a sense of her Zambianness. I wanted her to be rooted here before she experiences the rest of the world," she said.

Rungano Nyoni on Success, Sexism, and the Fight for Creative Control

After the success of I Am Not a Witch, which premiered at Cannes and earned a BAFTA, Rungano didn’t rush into her next project. She wasn’t sure she would make another film at all. "I’d stopped writing," she said. "I Am Not a Witch was hard to make, and I felt drained."

And with success came pressure—something she felt more acutely the second time. "Everyone had ideas about what kind of filmmaker I was supposed to be," she said. "There were expectations from financiers, collaborators, critics, and I started making choices based on what others wanted, but I’ll never do that again."

Despite her accolades, Rungano feels far from successful.

"I’m grateful for the opportunities I’ve had and feel lucky to do what I do, but success, for me, would be making films without being constantly questioned—the way my male peers are just allowed to direct. I have the accolades, but not always the respect. One male peer who has made fewer films than I told me he’s the alpha and omega on his set. That’s what I want—to have that authority."

She sees a gendered hierarchy even among African filmmakers. "Being a woman is the hardest part," she said. "Black male filmmakers still have it easier. Being African, being a woman—being both—becomes more complicated."

Despite the challenges of being a filmmaker, Rungano isn’t done yet. She plans to make a sci-fi film—surreal and playful, yet meaningful. "Sci-fi is my favourite genre, so I want to have fun with it," she said. "But not empty fun. I must find meaning in it, even if it’s not a heavy subject."

She was unequivocal when asked what advice she has for emerging filmmakers, including those from Zambia: "Don’t wait to be discovered. Just make the film. Use your phone. Use your friends and family as actors. Share. Upload your film to YouTube if you can’t afford to submit it to Cannes. Don’t just talk about it—do it." She added, "I receive many requests for mentorship, but I only agree to help those who have something to show, even if it’s only a script."

Her vision is clear—even when the world around her is murky. "If I only had one more film to make, I’d still make it here," she said. "I believe Zambia is where I’m meant to be."