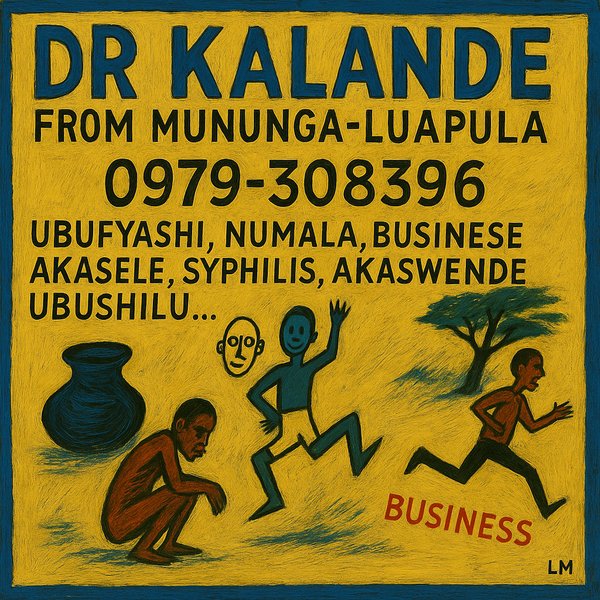

Amongst the bulletin boards and plastered walls of Zambian streets, between the commercials for cool drinks and real estate, sit advertisements for traditional healers. In bold word art fonts, they broadcast the ailments they can help you with, from help with illness to court cases to marital issues. But as much as these posters of traditional healers or ng’angas sit visibly, the practice remains an obscure part of Zambian culture and is steeped in the deepest of taboos.

Technically, ng’angas are defined as herbalists, diviners, and spiritual healers. They are regulated by multiple associations, trained and examined in their knowledge of traditional herbs, and much like Western-trained doctors, follow an ethical code and have a body to answer to. But heard on the streets of Lusaka, the term has become synonymous with witchcraft and is feared just as much.

History of Ng’angas

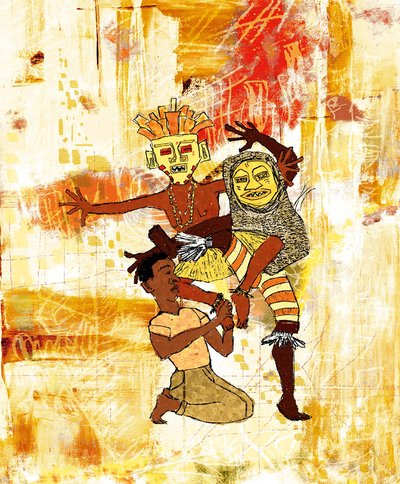

It wasn’t always like this. Like many other aspects of Zambian life, things were different before colonial rule. The religious beliefs of pre-colonial Zambia were rooted in African traditional religion, the main tenets of which involved relating to the natural environment spiritually, turning to nature as a source of both physical and spiritual healing, and seeing it as a place embodied with spirits of its own. As much as there was a belief in a higher deity, whose name differed depending on the language you spoke, the emphasis was on spirits found everywhere, including those of the ancestors. Having once walked the earth, these spirits were seen as actively involved in worldly affairs and could bestow blessings or misfortune, depending on how they saw fit.

In this period, ng’angas were highly revered and were even advisors to chiefs and leaders on both physical ailments and community affairs. In short, ng’angas had power. And after the arrival of colonialists, it was this same power and influence that made them a threat. Colonialists, fresh from their own witch trials, were the ones who labelled ng’angas as witchdoctors, belittled their practices and indigenous knowledge, and greatly undermined their social standing. Zambia's Witchcraft Act, enacted in 1914 during British colonial rule, criminalised practices associated with traditional healing.

The Role of Traditional Healers in Modern Society

Since Zambia was declared a Christian nation, consulting ng’angas has increasingly become a taboo. Many see their practices as conflicting with both the nation’s Christian values and its identity, and many see their practitioners as malignant or con artists. But the fact that ng’angas are sought out in secrecy doesn’t mean they aren’t being consulted.

A study done in 2021 in Lusaka’s Kalingalinga suburb revealed that 70% of its inhabitants believed in the powers of ng’angas, and many had and would turn to them for help regardless of the Christian denominations they belonged to. A 2005 study found that 70–80% of individuals in Zambia who experience mental health issues initially consult traditional healers before seeking assistance from conventional healthcare providers.

Much like medical doctors and nurses in Zambia are governed and regulated by the Health Professions Council, traditional healers fall under several bodies, such as the Traditional Health Practitioners’ Association of Zambia (THPAZ), the Zambian National Council of Ng´angas (ZNCN) and the Zambian Herbalist United Organisation. These associations primarily focus on registering, regulating, and evaluating traditional healers at both national and regional levels. They aim to promote traditional medicine as a cultural heritage and, most importantly, to provide safe, high-quality, accessible, and affordable primary healthcare. Some of these associations also support scientific research into herbal medicines and collaborate with the Ministry of Health, the WHO and USAID. Traditional birth attendants today are found to operate at the level of primary health care providers.

THPAZ is the largest of these bodies, with over 40,000 registered members. Under THPAZ, an individual must have at least a primary school education and be a legal adult to pursue a career as a traditional healer. They are required to apply for and renew a competence certificate every five years. Members of THPAZ must also undergo an attestation procedure to demonstrate their knowledge of traditional medicine and the specific skills required to be a ng’anga. This test includes the ability to recognise at least 30 different herbs and the submission of two medicines prepared by the ng’anga, which are then tested for their effectiveness.

There are several practices considered illegal by THPAZ, which can lead to hefty fines and the loss of a traditional healer's registration. These range from publicly advertising services—based on the belief that customers should be drawn to traditional healers by their skill—to selling traditional herbs in open-air markets, as it's believed this practice contaminates them. More serious offences include engaging in practices that can cause harm to others or accusing a community member of being a "witch" responsible for harm.

The Tension between Traditional and Western Medicine

The 2005 Zambian Mental Health Policy indicated that 70–80% of individuals experiencing mental health issues initially consulted traditional healers before seeking assistance from Western healthcare providers. This tendency to view traditional healers as the first line of defence, both spiritually and physically, has been a source of tension between healthcare providers. Western health professionals often place blame on traditional healers when patients arrive at hospitals and clinics too late to receive effective assistance.

In 2016, midwife Chileke Yambisa of Lundazi District Hospital noted that the hospital continued to record high rates of maternal deaths because pregnant women preferred to consult traditional healers first, even in the face of complications. Often, they only arrived at the hospital when it was too late to assist them.

The Danger of Dismissing Indigenous Knowledge

A longtime defender of Zambia’s Indigenous knowledge systems, Dr Gankhanani Moyo emphasised the power of language in shaping societal attitudes toward traditional healing:

“They are not traditional healers — they are healers,” he stated. “It's like the role of Blacksmiths. But we do not call them traditional blacksmiths. These adjectives have been brought in to try to qualify because we do not see them as healers. Already that reduces their position; we start looking at them from that angle, and language has been used to do that.”

Dr Moyo further stressed the deeper consequences of marginalising these practitioners: “The moment we cut them out of society, we have cut out our knowledge, a special knowledge, our heritage, our identity. We have cut out who we are. We are losing the knowledge that actually can help us progress. And why should we lose when we know that we are benefiting from it?”

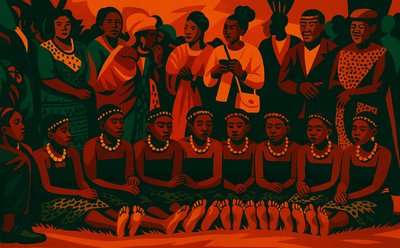

In an age where Zambians, more than ever, have consciously tried to roll back the effects of colonialism, have partaken more and more in traditional ceremonies, and are increasingly likely to be seen in indigenous hairstyles and attire, why is this the one facet of our ancient knowledge and identity that remains taboo?