Examine the symbolic weight of English as both a tool and a tether, the untranslatable soul of indigenous tongues, and the intimate, everyday diplomacy of code-switching. Through travel, memory, and local interaction, the article thoughtfully unpacks how language is not merely a means of communication but a living, breathing record of who we are.

"And the Lord said, Behold, the people is one, and they have all one language, and this they begin to do, and now nothing will be restrained from them, which they have imagined to do. Go to, let us go down, and there confound their language, that they may not understand one another's speech." – Genesis 11:6-7

Floating on a cloud of hope and post-pandemic wanderlust, my most dear friends and I ventured on a girls' trip to Zanzibar. It was 2022, the airport smelt of hand sanitiser, and we kept our masks and vaccine certificates close as we navigated a new form of travel anxiety. From plane to bus to ferry to motorbike, we bartered English for Swahili in a strange land to get what we wanted most: adventure.

If you ask me now, I do not know how we did it. Somehow, we were audacious enough to trek to a strange tourist town, catching and trading words along the way. Mambo. Habari. Elfi Ngapi. Nzuri. Asante. Baridi because beer must be cold.

Language is kind to me, so I transposed pieces of KiSwahili I heard in songs to the bazaar as I bargained for trinkets and pieces of art to carry home and to the night when adventure called us out to the beach and to the small bars tucked inside the local markets. We wanted to see how residents of the coastal tourist town lived after the ever-smiling business hours.

One Kilimanjaro here, two Tuskers there, and we started to speak with more than words: we spoke with smiles and leaning compliments, offering a new loyalty that would expire at dawn when we retreated to our real lives. On a whim, the DJ, a sinewy man choking a microphone behind a laptop, dared, "Give us a song from Zambia." I froze for a second before I pieced together his meaning; he was not asking me to sing, he was requesting a song.

"Amarula by Roberto!" I shouted. YouTube whirled to life, and without buffering a second, the beat blared through the speakers, pouring its steady bass rhythm into the tiny tavern. Amarula, playing on a loop, lured patrons to sing Nyanja lyrics they could not speak. We left them staggering to the familiar thump when we slipped away into the salty night. I count that moment as my first act of diplomacy.

Language as Identity

It was a restless era; I packed my rucksack and budgeted on the go as I stole pieces of everyone I encountered. Maybe I was finding myself by escaping everything familiar, including language. As our official and global lingua franca, English does not command attention like it should. The answer to a greeting is a mechanical "fine", and every positive experience is described as "nice". Outside of English, there are new ways of greeting, new answers and descriptions that sparkle.

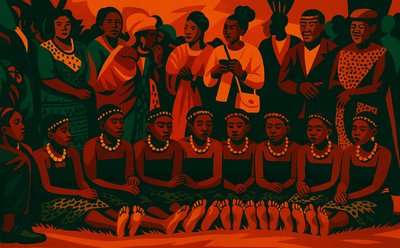

In Zambia, most people have the same congenial way of being, but every regional dialect brings something new to the table: "Good morning", when translated well, becomes "How have you risen?" or "Did rest find you?". It is more poetic and more definitive, and that is why I find that good translation is an art that can enrich English and further our understanding of who we are as indigenous Zambians.

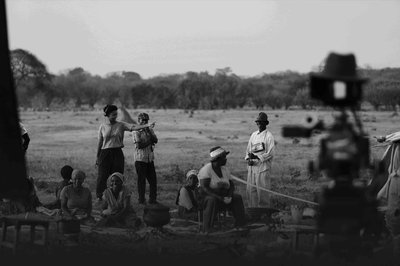

While I explored Zambia, I discovered that our intercity roads have the rhythm of a beating heart, rising to peaks of activity with bomas, markets, and agro-dealers before they fall to bush, thickets, and wide, quiet expanses of undeveloped land. In between are bright, captivating produce markets, and even when I have no plans to buy, I stop and listen to the eager women who swarm, buzzing in their lyrical pitches, claiming whatever they are selling is the best, sweetest, freshest.

Can I speak Lamba? No, but the women on the Great North Road around Mkushi bring it to me, and I carry it home with their sweet potatoes, mushrooms, umumbu and cassava. Back in Lusaka, the freshness disappears and is replaced by the sharp burnt scent of the city. Here, Lusaka combusts the poetry of language into commands. Muli bwanji (how are you?) becomes Bwa – its brief, quick, capitalist alternative.

In the Beginning was the Word

In the beginning, which for Zambia is 1964, Kenneth Kaunda had a dream, a dream that one day we would be One Zambia, One Nation. This sounds easy in theory, but Zambia is a landlocked nation living with her arms wide open, welcoming refugees and immigrants on the right and aid on the left. I was raised by civil servants and often heard my parents bend their tongues to meet their clients' points of need at the international curb of languages, Home Affairs, while outside, women sold fruit and vegetables in Bemba, Tonga, Chewa, Lozi and Kaonde.

Today, a conversation between my mother and I will often sound like, "Mama, bushe muli na gown yangu ya black? Nali ii chefya to attend a dinner" – it is a multilingual mashup, chasing competence and drama over tribal loyalty. Some words are comfort words, others are phonetically easier, while some are chosen because of family history and inside ways of being.

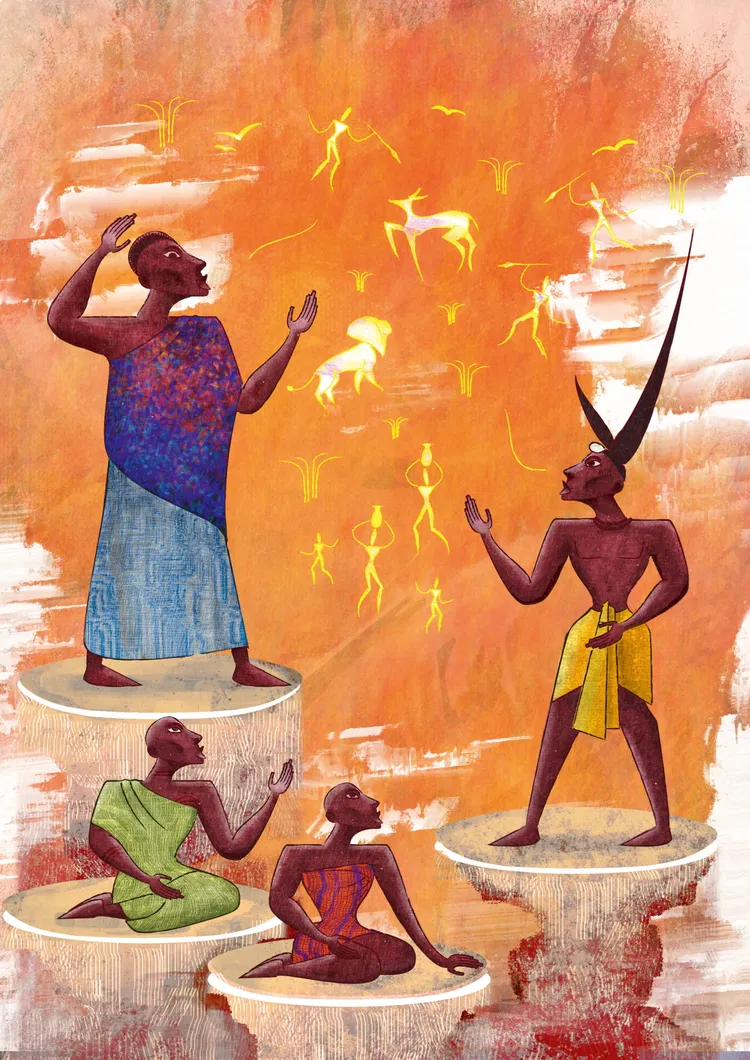

Zambia was KK's own Tower of Babel. He threaded citizens from every point of the country into the tapestry of one strong, united nation. While geography is the map of language, there are exceptions to the rule. On my travels, I met a man whose opening joke was that his name was HH, Herbert Haazembe. Herbert spoke seven languages and understood nine, Ndebele among them.

Herbert told me about his life around Rhodesia, sending and receiving telegrams through the post office. He laughed about how it would have been cheaper and easier to send "Cow is Dead" instead of the Ing'ombe Ya Zimina that his family would understand. He spoke of how Zambia’s propensity for asylum and open borders brought Zimbabwean languages into his life through the people who carried them.

Through him, I saw that language could never really be separated from us. When we are angry, happy, in love, or in trouble, our true selves escape and echo through our words. Our thoughts are private, but abrupt triggers like road rage can expose the language of our minds.

The Language of Power: The Aspirations of the English Language

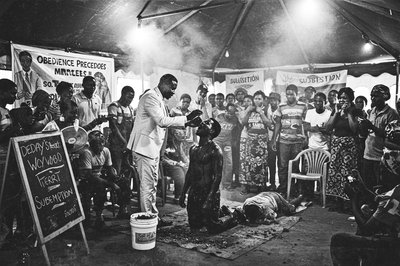

As an ambiguous-looking and -sounding Zambian, I say nothing and observe which language people engage with me first. Geography is a reflexive guide for most people, but in a formal setting, English is the top-shelf, accessible choice, and even people who are not fluent reach for it. English has a religious history for us Zambians, arriving with the missionaries who set up posts and schools to bring us God, Western healthcare and education.

Missionaries quickly understood that they needed to learn our mother tongues to be able to spread the good word, so they developed hybrid learning systems to teach Africans scripture. English-speaking settlers relied on the work of missionaries to provide the Africans who worked for them with basic reading, writing and numeracy skills. Under British rule, the few Zambians with a better grasp of the English language than their peers were rewarded with positions in civil service as kalaiki, kapitano and kapaso – clerks, captains and messengers – thus handing them an elevated social status.

Post-independence, the government introduced the New Primary Approach (NPA), which was supposed to enhance English communication skills in learners by emphasising situations and contexts in teaching. This emphasised group work among learners rather than the teacher being at the centre of the lesson. It further proposed that this teaching approach promoted the 'Zambianisation' of English as learners developed their accents, often quite different from their (white) teachers. But in 1966, the Ministry of Education issued a policy document (Educating Our Future: National Policy on Education) which retained the use of English as the official language of classroom instruction. This still stands today, and it is no wonder that English is aspirational and remains viewed as the language of the enlightened.

Contextual Vulnerability: How Language Changes with its Environment

Orthographically, Zambian languages are very different. Bemba, for example, has many fused words and nasal pronunciations that are fundamentally different from how words are fused and pronounced in Tonga. To unite a nation and ensure literacy, it is clear to see how English was the practical choice at the time. Language is flexible, altering itself to its environment. This can be seen in the linguistic flexibility of the urban Nyanja of Lusaka Province and the urban Bemba of the Copperbelt.

When left to our own devices, we experiment and alter language as we seek out understanding. In the hum of a market in Lusaka, I am greeted with city Nyanja, and whenever I respond in English, I am labelled Ba Some Of Us and pay for it with higher prices and reluctant negotiation. Elders defer to whatever they assume my mother tongue is among the top seven – nobody has ever guessed that I am Namwanga, a smaller, less prominent tribe from the North. Few people speak it, and even I only have the chance to when I giggle into the phone to Nakamba, my grandmother.

If language had the resistance of brick and mortar, we would have built it in concrete and saved our meanings and intentions forever. The Egyptians tried, and even that didn’t hold. Unlike other tangible parts of us, language has no measurable beginning or end and, as a result, cannot have a determining expert. No human is above the other; similarly, no language is above the other, but each has a specific role it plays in service to the equilibrium of the whole.

Economics and mathematics both have finite ends and objective means of determining who is qualified to decide what is good and bad. Language is too intimate and vulnerable for this. A made-up word between lovers or the babbling of a baby is just as valid as a cliché written into a policy.

The Tower of Babel is a story from the Book of Genesis in the Bible that narrates how humanity, speaking a single language, had an ambition to build a tower to heaven and make a name for themselves. God interfered by planting new languages among them, scattering their own. It was not their national development plan that was wrong; their new inability to understand each other was the seed of their doom. God’s strategy was genius.

Language is flexible by nature, and this is the source of its strength and fragility. When something is wrong in a written code, technology glitches and crashes, but language can resuscitate and remould itself even in its most broken form. Language can decay, but it is full of tangible intangibles that can make it live on. The wrong hand gesture can render an eloquent speech untrue, while a well-placed nod can foster trust and loyalty.

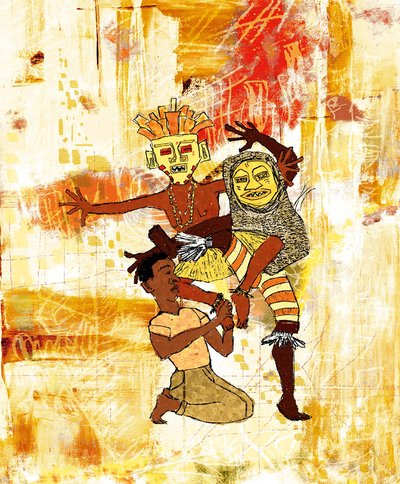

Through Bemba marriage rites, we are exposed to how Zambian languages are more than mere communication tools; they are vessels of culture, history, and identity. The Cisungu and Imbusa are rites of passage deeply rooted in oral traditions, with teachings imparted through dance, song, and storytelling. Each symbolic act is loaded with meaning, and the teachings are not merely academic; they are experiential, transmitted through shared language and context.

Their true meaning may carry connotations of violence or malevolence when translated because history, ancestry, spiritual guidance, and protection have different importance in indigenous languages. During Ukusanshya Amafunde, the bride and groom are encouraged to share what they have been taught, and there is no obscenity in the overt sexuality and intimacy of their teachings. Such lessons can lose their depth, and their meaning can be altered when translated. This demonstrates that at some point, we have to accept that some indigenous experiences have no English equivalent and vice versa.

Code Switching to Be Understood

"The most basic of all human needs is to understand and to be understood." – Dr Ralph G. Nichols

For hospitality, self-defence and personal enrichment, we adapt our language patterns to bridge with others and show that we have no intentions to harm or be harmed. We speak from what is available and accessible, and that is why some languages prevail over others. Exposure plays a huge role in the life cycle of a language. English, while widely used as a medium of instruction, does not always carry the full emotional range or cultural context found in indigenous Zambian languages. That is not a bad thing.

In an extensive Saturday morning conversation, Professor Serpell shared enlightening insights about the progression of language in a person’s lifetime and how the words we use interact closely with who we are. We explored why some people are more comfortable delegating responsibility or expressing frustration in English than in their Zambian languages. This is not merely about competency; context, values and intention influence language as much as education does.

Informal means of expression have crept their way into academic papers, with their translation based on intention rather than objective meaning. Saying that someone "is no longer with us" is softer and kinder than saying they are dead, and this is something that is reflected in both English and indigenous Zambian languages.

Language as Bridge

What I have come to understand through my journeys – across Zambia and foreign shores – is that language is both a barrier and a bridge. When Roberto's Amarula had Tanzanians singing Nyanja words they did not understand, something magical happened: a connection without literal comprehension. Similarly, when I carry home Lamba phrases with my sweet potatoes from Mkushi, I am transporting more than words – I am bringing back cultural context, human warmth, and a sense of belonging.

Our multilingual reality in Zambia is not a problem to be solved but a richness to be celebrated. The code-switching, the urban evolutions of traditional languages, and the melding of English with indigenous expressions – these are not signs of linguistic degradation but of cultural vitality. Like Herbert Haazembe with his seven spoken languages, we navigate multiple worlds through our words, each offering a different facet of identity and understanding.

In the end, KK’s Babel has succeeded, expanding horizontally, creating connections across landscapes, generations, and cultural boundaries. How we say things and when we say them can matter as much as how we squeeze out toothpaste, but whether we decide to let that unite or divide us is entirely up to us. We are in charge, after all, so let us talk.